Julie Green

In the bucolic town of Corvallis, Oregon, on her peaceful street, in her picture-perfect home, after tea and cookies… Julie made me cry. The tears came unexpectedly while staring at the list of death row executions on the Death Penalty Information Center site that she was showing Klea and me. I felt embarrassed. But Julie looked at me and said, “It’s good to see you react so strongly.”

Hard-hitting experiences often happen in the most unlikely of places. I’ve always known this to be true, but our WESTERN EDGE trip really drove it home. On the road there is no predictability, no real routine, and even the most run-of-the-mill moments take on a memorable quality. For example, I will forever remember a gas station conversation I had with a stranger in O’Brien, Oregon because while standing there I knew I’d never see that wide smile and rumpled, generous looking face again. As we drove in and out of each town, meeting all kinds of people along the way, I realized my expectations were always overturned, thrown off course, or done away with completely. So by the time we reached Corvallis to meet with Julie I had learned to assume nothing… but still she brought way more to our visit than I had bargained for. As did her exhibition The Last Supper: 500 Plates that we were lucky enough to see and document at Marylhurst University’s The Art Gym. Nothing can really prepare you for the experience of that installation— 500 blue and white plates, all hung together, of the final meals of death row inmates…some simply stating “made no last meal request.”

Julie didn’t show us the list of death row executions to shock us— viewing that list is an integral part of her daily practice when she works on The Last Supper, an ongoing project that currently consists of 552 painted plates of last meal requests from death row inmates (and that she is committed to continuing until capital punishment is completely abolished). During our visit Julie took us through her entire process step-by-step, beginning with her daily online research to letting us watch her paint a last meal in cobalt blue on a carefully chosen second-hand plate. Whether she’s working on The Last Supper or her more personal narrative paintings, an established routine is essential to her art practice. She splits her year up quite practically, alternating every six months between The Last Supper and her narrative work, fully focusing on one project at a time. In talking with Julie about her work it’s apparent nothing is rushed; details are executed laboriously, decisions are carefully weighed, opportunities are taken deliberately, and in between each uttered sentence she allows herself long silent pauses to find the right words.

Another thing I noticed— Julie doesn’t really speak for her work. Throughout our entire visit she never directly spelled out her thoughts on The Last Supper or even her narrative paintings and she certainly didn’t talk much about what she specifically hopes to elicit in her viewers. Instead she told anecdotal stories about experiences she had that provoked questions for her; questions that ended up prompting her different bodies of work, and that perhaps still remain unanswered… But what the stories she told revealed is that sometimes even when you get an answer, you have to keep asking questions. This is the story she told us when I asked how The Last Supper started:

I was living in Oklahoma and I would read the morning paper. In the paper they would print about the executions that had happened the night before. They would print who it was, what they were wearing, and what they had for their final meal. I hadn’t thought about final meals before. I guess I knew we had them, but I hadn’t given it much thought. Seeing that in the newspaper first thing in the morning, well, I had a lot of questions… When I started this project the first phone call I made was to the newspaper and the prison and I asked “Why is this in the paper” and both the press and the prison warden said, “The public wants to know.”

That answer was a can of worms, obviously prompting more questions for Julie instead of silencing them. It elicits so many questions for me, too… regarding our justice system and death row, the ritualistic aspect of meals and our relationship to symbolic social acts, our shared morbid curiosity, the politics of comfort, punishment and death, and the issue of humanizing everyone no matter what they have done.

Even now, far away from Corvallis, The Last Supper still makes me want to cry.

How would you describe your subject matter or the content of your work?

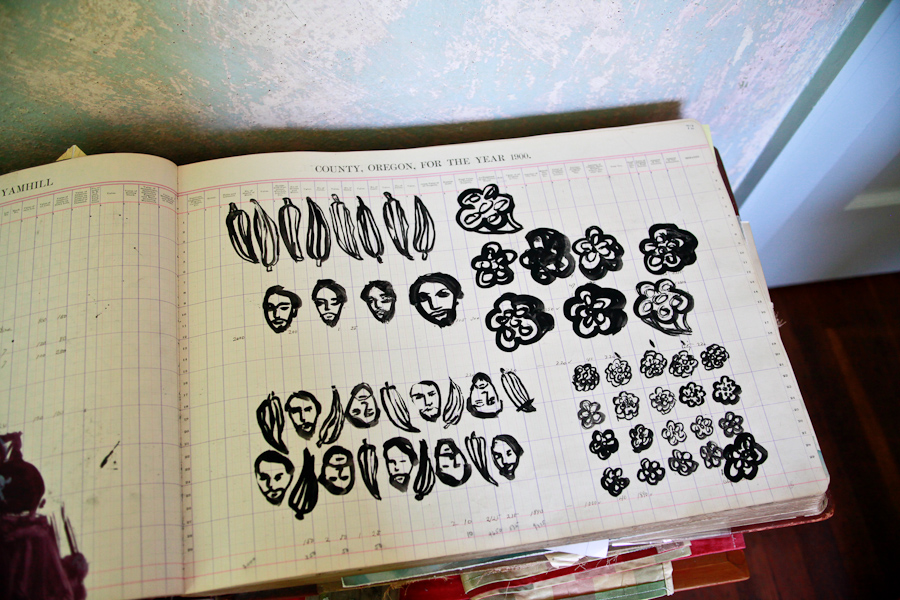

Half of each year, I paint The Last Supper, illustrating final meal requests of U.S. death row inmates. The other six months, I work on other paintings, in full color, about life. For my narrative work I keep a big ledger book that I put all my ideas in so that I remember them. Much of this imagery is evoked from memory so everything looks a bit dreamlike. For The Last Supper, I have a book in which I’ve collected images, cut out of grocery store fliers, to refer to while painting food requests.

What mediums do you work with?

Idea equals material. It depends on the project. Lately, I am using a lot of mineral paint on plates, as well as egg tempera on panel. For The Last Supper, cobalt blue mineral paint is applied to second-hand plates then kiln-fired by technical advisor Toni Acock. It turns out that blue is the most difficult mineral paint to apply. Luckily, I didn’t know this when I began! Blue on white ceramics feels and looks right to me. My approach to the process is a bit art brut; I’m not following the traditional, thin layering techniques of china painting. Acock’s expertise is essential in firing my thickly applied paint.

You have quoted Andy Warhol saying the artist of the future will simply point… and stated that you paint to point— can you tell us more about this intention?

I am inspired by contemporary society. I research, and then I point. This is true for The Last Supper as well as the narrative paintings and Wallpaper.

Your ongoing series, The Last Supper, has been a thirteen-year pursuit to reveal the humanity on death row through intimate portraits of last meal requests painted on ceramic plates. How did this project begin? When will it end?

Oklahoma has higher per capita executions than Texas. I taught there, and that is how I came to read final meal requests in the morning paper. Requests provide clues on region, race, and economic background. A family history becomes apparent when Indiana Department of Corrections adds “he told us he never had a birthday cake so we ordered a birthday cake for him.”

States with the highest numbers of executions make up the bulk of the series. Texas recently had its 500th execution, a black female. Texas is the only death penalty state that does not offer a final meal selection; they now serve the standard prison meal. California has few executions, but has a huge death row population. This year, to point a finger at California, I painted twenty Folsom State Prison menus from 1896-1955.

Now that there are 552 plates, shipping and installation of fragile ceramics is quite an undertaking. I am looking for a library or a university or a museum- in Texas would be great—to donate the project on a ten-year loan. The Last Supper is not for sale.

I plan to continue adding fifty plates a year until capital punishment is abolished. A poet asked if I ever get tired of painting lumpy blue food. No, I don’t.

Besides your art practice, are you involved in any other kind of work?

I am a Professor of Art at Oregon State University, where I’m blessed with amazing students and terrific support for my research. I garden organically and produce many of the fruit and vegetables we consume, practice yoga daily, and am an environmentalist, putting more miles on the Gazelle bike than the car each year. I try to contribute in positive ways. As my yoga teacher Sujita says, In the end, it just comes down to service.

What are you presently inspired by— are there particular things you are reading, listening to or looking at to fuel your work?

Less, rather than more. I attempt to set up life to have few distractions: no TV, no sofa.

My husband Clay Lohmann is the greatest inspiration in my life. We have been together 25 years. He is my best critic and best friend. We were both trained as painters, and now use traditional craft mediums. He quilts, I paint on ceramics. Clay is my personal librarian, and brings me stacks of new editions from our wonderful downtown library. I read a great deal of non-fiction. This week I am reading Matthew Goodman’s Eighty Days, a fascinating and accurate account of two women journalists’ 1889 race around the world. Eckhart Tolle’s A New Earth gives me hope. Several other books that are important to process are Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, Joe Brainard’s I Remember, and The Essential New York Times Cookbook– only Amanda Hesser can write a timeline that makes you laugh aloud.

What does having a physical space to make art in mean for your process, and how do you make your space work for you?

Art making is a meditation for me. Having a clean sparse studio with northern light is my ideal, and that is what I have.

Is there something you are currently working on, or are excited about starting that you can tell us about?

Yes! Set is a series of narrative plates, each displayed in front of an accompanying painting. By placing a painted porcelain platter directly in front of a completed egg tempera panel, I am critiquing the hierarchy of Western materials and techniques. Oil paint, egg tempera, and bronze have long been considered the high-art mediums in the U.S. and Europe. Mineral painting, on the other hand, is marginalized as women’s work, a craft often delegated to Christmas ornaments. Ceramics set in front of the panel also obscures the “real” painting. We are forced to rubberneck to see it. These retables depict events that are both personal and political, such as Ronald Reagan and Me. In high school I was a lifeguard at Greenwood Pool in Des Moines, Iowa. Ronald Reagan was a lifeguard at the same pool fifty years earlier; we sat on the same stand. The plates are functional and made to be used. We eat pecan bars off Ronald Reagan’s chest, while his mate, the painting on wall, looks on.

Which other artists might your work be in conversation with?

Besides Clay, I am in conversation with Roger Shimomura, Lisa Cole-Kronenburg, Rachel Hines, Deborah Brackenbury, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, and Don Kottmann about my work. Giotto, Goya, Fay Jones, and Judy Chicago are important influences.

Specific to the final meals, many others are doing work on final meals and Pete Brook has a comprehensive list on his site. Pete Brook— The Last Meals of the Executed: A Selection of Projects in Photography and Painting.

How do you navigate the art world?

Slowly.

I have much to be grateful for. Recently I was honored to receive a Joan Mitchell Painters and Sculptors Grant. It is encouraging for a painter working quietly in Oregon to be noticed by a major New York art foundation. Friends have said my receiving this award restored their faith in the system. In the past few years, The Last Supper has generated a great deal of press, far more than I ever imagined it could. Recognition can be stressful. The night before an interview with Kirk Johnson of The New York Times, I was so nervous I almost threw up. The curator Deborah Gangwer once told me something that has helped with public speaking; she said “It’s not about you, its about the work. Honor the work.”

It can be challenging to find a balance. Because of my opposition to capital punishment, it is easy to promote that project. The narrative paintings, while also political, are subtle. It is a current goal to find more opportunities to exhibit the Set narratives.

Words of wisdom?… a motto, favorite quote?

Studio practice is just that. It takes focus and commitment. Unless your mother is in town visiting, I recommend spending at least three hours, six says a week, in the studio making work or staring at the walls. And don’t have your computer in your studio.

Two quotes I live by:

Stare, pry, listen, eavesdrop.

Die knowing something. You are not here long.

—Walker Evans

If the only prayer you said in your whole life was “thank you,” that would suffice.

—Eckhart Tolle

By the way, thank you for your interest in my work.

Are you involved in any upcoming shows or events?

Oregon State University Faculty Exhibition, Corvallis, group show through October 9th 2013.

The Last Supper: 550 Plates Illustrating Final Meals of U.S. Death Row Inmates, Lore Degenstein Gallery, curated by Dan Olivetti, Susquehanna University, Selinsgrove, PA. Solo show January 18th through March 1st 2014.

To Shoot a Kite, curated by Yaelle Amir, CUE Art Foundation, New York, group show, summer 2014.

Where can people see your work?

Narrative Painting

The Last Supper

The New York Times

Oregon Art Beat

Dark Rye Documentary

Pingback: Dead Man Eatings: Julie Green in ‘In The Make’ | Prison Photography