Our Last Hurrah: Larry Bell

I suppose it’s true what they say, all good things must come to an end. IN THE MAKE began on a whim, a sudden thrilling impulse that grew into something much bigger and bolder than Klea and I had initially imagined. And now, almost four years after its inception, with just one last WESTERN EDGE studio visit to publish, our wild and wonderful venture has come to its natural conclusion. Though we will no longer continue with our ongoing documentation of artists in their studios, the ITM site will still exist as an archive. We have a bit more to say about all this, so please read our final field note. But, for now… let’s usher in our fantastic final act.

Always go out with a bang, that’s what my father liked to say. And certainly, for us, there is no bigger bang to go out with than Larry Bell. When we were planning and booking studio visits for our WESTERN EDGE trip (which now seems like ages and ages ago) we were astonished, and maybe a tad giddy, that Larry said yes to us. It seemed too easy, too good… and so it was with much anticipation that we arrived at his studio in Venice, which is just a stone’s throw away from the beach. Though Larry just recently informed me that he has moved to a much bigger and nicer space, it’s hard to imagine anything better than the studio we visited him in— huge windows, tall ceilings, an airy, open feel, and those black and white tiled floor that I fell in love with. He welcomed us wearing his signature hat, smoking his signature cigar and after a quick tour of the space we settled into conversation. Jay Belloli, a curator and friend of Larry’s hung out too, as did Larry’s brawny looking pitbull called Pinky.

Larry has been making work for 53 years and is often associated with the Light and Space Movement and West Coast Minimalism, but when asked about these associations he said they don’t necessarily figure into how he thinks about his own work, but that “any interest in the work I’ve done is appreciated, wherever it comes from.” Over the course of his career Larry’s work has rigorously considered the properties of light on surfaces, and he continues to experiment with these interplays of light and surface and their interactions with surrounding space. During our visit he showed us his newer sculptural works called “Light Knots” in which sheets of acetate are coated with vaporized metallic particles, cut and looped into iridescent “knots”, and then strung up from the ceiling to lightly sway, refracting light with each slight shift in position and time. He also showed us recent collages— made from layers also coated in vaporized metallic particles, these pieces bring together materials like paper, fabric, acetate, and Mylar to create seemingly smooth swathes of luminous colors that appear to change from different angles.

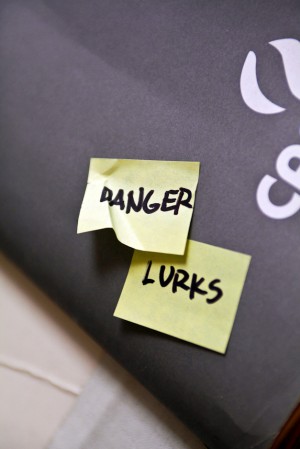

Despite his oft-referenced place among the leading and influential figures associated with the Light and Space Movement and West Coast Minimalism, Larry doesn’t spend much time waxing nostalgic about past works or heyday moments, instead he is entirely focused on the present. All his attention goes to the work he is compelled to make now, and he seems to allow himself the freedom to follow the many different incarnations of his curiosity, without restraint or judgment. Throughout our interview Larry reminded me (humorously) that, “danger lurks everywhere” … but you’d never guess he thought that way… or maybe it’s that he knows just because the danger is there, it doesn’t mean you have to be scared…or… that being scared is part of getting somewhere good.

How would you describe your subject matter or the content of your work?

The content of the pieces is about spontaneity, improvisation and intuition. Those are the tools that I have put to work here in my studio in Venice, and in my studio in Taos I’ve put those tools to work plus the facility of the mechanical equipment in that studio to generate the components of these pieces. So the parts are made spontaneously, improvisationally, and intuitively and then used in the same manner to make their statement, whatever that is. I’m not concerned with the statement. The work doesn’t give a shit— what it is, or who is looking at it, it just does its thing, irrespective.

What mediums do you work with?

My media is the interface of light and surface, my normal substrates are glass and paper. The material is about light— it reflects, transmits, and absorbs light all at the same time. When I improvise with it I put coatings on it that alter its ability to do those things, so the compositions are totally random but the technique is not at all random.

Your work is associated with the Light and Space movement that originated in Southern California in the 1960s— how do the environmental aspects of LA continue to inform your work?

They do not. But really, I’m thrilled to be considered a part of anything as I work pretty singularly. I don’t mind being considered a part of the Light and Space movement, and I don’t mind having been considered a minimalist, though I’ve never thought of myself that way. Any interest in the work I’ve done is appreciated, wherever it comes from. I don’t really talk about my work with my peers or other artists, I don’t really have a big sense of community, I’m kind of on my own trip and so are lots of my artist friends… we are all just doing our own thing.

Your work asks the observer to confront objects and spaces in a way that challenges assumptions about ordinary, natural phenomena. What kind of experience do you want a viewer to walk away with?

My work asks nothing of anyone except me. I have no assumptions about what people will think, do or participate with. I am not interested in any of these things. My work is my teacher and I learn only from its teaching. The answer of what to do next is always in the work done before.

What are you presently inspired by— are there particular things you are reading, listening to or looking at to fuel your work?

I like acoustic musical instruments. I don’t play them anymore, I just like to look at them. I like the expectation that it will provide me some kind of epiphany. I recently purchased a 10-string banjo made in China, don’t have it yet but looking forward to it. In my collection I have about 50 12-string guitars. I like double strung instruments because I am very deaf.

I think of my work as my teacher, so I’ve just been a student all this time. I went to school at Chounaird Art Instititute in Los Angeles (which later became CalArts) originally thinking I was going to get into animation and go work for Disney. But the school had a mandatory painting class and in that class I became really taken with the painting teachers. Something about the style of their lives was much more interesting than people that were training for a job. These people had a job teaching but they weren’t teaching you anything other than how to trust yourself, and that ultimately is the most important thing someone can learn.

Robert Irwin was one of my teachers at Chounaird— his first semester teaching was my first semester attending, and he just became my hero. And as far as I’m concerned he is still my teacher.

What does having a physical space to make art in mean for your process, and how do you make your space work for you?

Because of the specific demands of my work I have to alternate between my studios in Taos and Venice about every three weeks, so I’m constantly traveling between the two places. I recently bought myself a new Suburban for my Taos/Venice run. The ancient one (’99) has 400,000 miles on it from those drives, it still runs great so I will keep it and have the luxury of two cars.

There are things that I can only do in Taos, and then only things that I can do in Los Angeles. I like to be in Venice because people have more access to me here— which is important as there is value in being able to share your work and ideas with people who are interested and want to discuss it. All the equipment that does the plating is in Taos, so I can only do the surface treatment for my work there. I’ve been in Taos since 1973 and my studio in Venice (through a twist of fate) now happens to be the same studio I had in the 60s.

Is there something you are currently working on, or are excited about starting that you can tell us about?

Yes, there is. Recently I have been engaged in works I call “Light Knots”— in which I improvisationally use a knife (much like one would use a pencil) to cut into the open page plane of Mylar laminate which allows me to twist it into a shape that I couldn’t get it into otherwise, and then I color it in a spontaneous way. These “light knots” are then suspended from the ceiling where they move and dance and play with light. I like the enormous complexity of these things but the simplicity of which they are generated is totally seductive.

Over the years how have you navigated your place in the art world?

Like a guy on a life raft with a refrigerator.

Nobody needs what an artist does. I think I heard de Kooning once say that the most important thing about his paintings is that they are totally useless. I like the spirit of that and I’ve tried to carry on the tradition of working outside of what people need. But of course, that has worked against me in a lot of ways. I had a very prominent dealer say to me that if I had stayed the course and continued on with my cubes I would have been rich. I never considered myself in business in the first place— riches were never part of my vision. I just wanted to be able to work and do my thing.

You have made work and had a studio practice for well over 40 years– can you tell about the sacrifices and rewards of this kind of commitment and endurance?

I have been in the studio for 53 years— it is all I know. I am celebrating my 53rd year of unemployment. Staying unemployed keeps me working. It is very hard on family and love. It can mean losing relationships with wife and children, parents and dear friends. It is painfully lonely and can be devastating financially. “Danger Lurks Everywhere”— that’s the truth, to me that’s the only thing that is for sure. Being an artist is just not a normal kind of life. There are no eight-hour days. There are 24 hour days, and that’s all there is. And that’s rough on other people.

To see more of Larry’s work:

www.larrybell.com